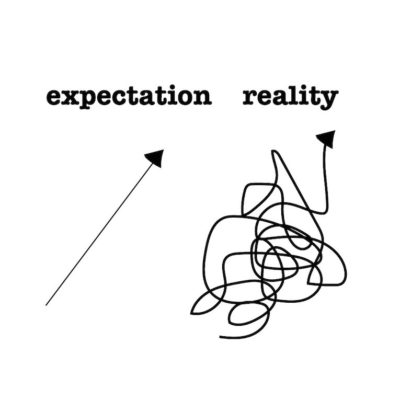

What do you mean my money didn’t consistently grow over 5 years? Whatever the investment, we all wish that we could rely on our money to grow at an expected rate, but the reality is more accurately represented below:

Economic theory of the ‘70s

The graph on the left reflects the 1970s attitude of traditional economics found in “Efficient Market Theory” (EMT), where it’s assumed that people act only to maximise returns and minimise risk, and that all the available information is reflected in historical prices. Under this theory, investors wouldn’t be able to purchase undervalued stocks or sell stocks at inflated prices.

Fissures to this theory started forming in the 1980s as stocks showed a lot more excess volatility than predicted by an EMT model – volatility that could no longer be explained away as just the ‘day of the week effect’. In modern markets, the inconsistency of this theory is even more abundantly clear, with results of a 2015 research study conducted by Dalbar finding that the average equity mutual-fund investor was underperforming the S&P 500 market index by a wide margin of 8.19%!

The problem with the EMT view is that it relies on the idea that investors are rational, have perfect self-control and make no mistakes. The reality is that when faced with uncertainty, people can be irrational, inconsistent and sometimes downright incompetent. We’re only human!

Enter ‘behavioural finance’

Forming a subset of behavioural economics, behavioural finance attempts to find a rational explanation for irrational market anomalies like bubbles and crashes – honing in on the emotions and cognitive errors of the very human investors. Economist and Yale academician, Robert J. Shiller deftly describes the field as finance from a broader social science perspective to include psychology and sociology. Having a better understanding of behavioural finance and recognising the common biases that can influence investors can help you 1) know the reasons behind market anomalies and how to avoid them and 2) possibly finding ways to exploit behaviours for a profit. As we will later discuss, these behaviours are common not only in stock markets but are prevalent across other market-based investments, including property.

Behavioural biases – how can we explain what’s happening in investment markets?

The human brain works in weird and wonderful ways. There are cognitive and emotional biases that influence our decision-making without us even knowing it. Some investors, for example, subconsciously tend to prefer investing in alphabetical order, adding reason for Google’s switch of stock names from GOOG to AAPL, operating under the umbrella company of Alphabet Inc. and placing them at the literal start of the alphabet. In the modern age, it explains why an indiscriminate tweet by Donald Trump has reverberating effects on the market index. (See Bloomberg’s interactive model connecting Trump’s tweets to the Dow Jones Industrial Average in real time).

Cognitive psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, thought of as the ‘fathers’ of behavioural economics, suggest that investors are influenced by 2 primary behavioural biases: cognitive and emotional biases. While there are too many behavioural biases to name in one article, we’ll break down some of the most common cases below. These biases are often discussed in the context of stocks but can be considered in terms of other market-based investments, like property.

“It’s frightening to think that you might not know something, but more frightening to think that, by and large, the world is run by people who have faith that they know exactly what is going on.” – Tversky

Cognitive biases

Cognitive biases result from memory and information-processing errors and explain the faulty reasoning involved in how people think. If you’ve ever been to the bank as the advisors try to explain the financial benefits of a product and you’ve nodded along, pretending to follow them as they break down the numbers, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that people tend to make mistakes when processing information related to financial decisions. Two examples of cognitive biases are ‘mental accounting’ and ‘anchoring’.

Mental Accounting

This is the phenomenon that explains why millions of adults waste thousands of dollars a year on unused gym memberships and yet those same aspirational gymgoers will refuse to spend that same money on their own Netflix subscription. Mental accounting is where individuals allocate their money into mental compartments and treat the money spent in these compartments differently. In the context of investments, this can be seen in financially counterproductive behaviour like funding a low-interest savings account to save for a new house while carrying large credit card balances.

Anchoring

Related to mental accounting, there’s ‘anchoring’, where individuals have an irrational bias towards a certain benchmark figure; whether this be their last buy or sell price or the market value. People become attached to this figure without considering changes in the market.

Anchoring bias can happen to the best of us. Even value-investing genius, Warren Buffett has lost big from anchoring. After buying a certain amount of Walmart shares, he stopped buying as it grew in price – anchoring on his previous buy price, thinking that it would come down shortly. He eventually bought more shares at a later date when it had increased even more, his bias costing him $10 billion USD.

Emotional biases:

On the other side of the proverbial coin, countless people lose money everyday as they let their feelings get in the way of their investing. Emotional biases result from basing reason on emotions during times of stress and can be difficult to keep track of since they occur spontaneously at the time a decision is made. Examples include overconfidence and loss aversion.

Overconfidence

Overconfidence isn’t exactly an occurrence localised to investing. 80% of students believe they’ll finish at the top of their class, 68% of lawyers believe they’ll win in civil cases and 100% of writers believe that adding stats to their article make them sound more credible. This same attitude pervades the world of investing, with investors adopting an ‘I know more about xyz than you’ attitude, overestimating the precision of their knowledge. Believing they’re perfectly in time with the market, this often results in excess trades.

Prospect theory (loss aversion)

Prospect theory, also known as ‘loss-aversion theory’ models how individuals express a different degree of emotion towards perceived gains compared to perceived losses. In other words, we tend to feel the pain of a loss twice as much as we derive happiness from equal gain. Consequently, people tend to take more risks to avoid the pain of loss than to realise gains, often holding onto losing investments in the hope that the price will bounce back.

This relates to ‘regret theory’ as, similar to the fear of loss, individuals anticipate regret and try to make decisions to avoid this. For example, you’ve thoroughly researched an investment and go to purchase it. However, anticipating that you’ll regret this decision if it later falls in value, you avoid buying to avoid the pang of regret. Instead, you buy something that everyone else is buying.

Weirdly enough, people feel less embarrassed about losing on a popular investment than an unknown one. This ties into the behaviour called ‘herding’, where, like sheep, investors simply follow the crowd without doing proper due diligence. Herding and the associated FOMO is often how market bubbles are formed, as seen in the likes of the Bitcoin boom, dotcom bubble and the housing market of several Australian capital cities in 2017. See our article on the nature of property cycles for more information.

What can you do as investors?

The more aware you are of your own biases, the less likely you are to be influenced, or at least you might be able to catch yourself in the act. While even the best of us can fall victim to the entrapments of our own minds, your best bet is to plan your strategy and end-game before going into any investment. Clearly define your timeline, level of risk-tolerance and investing objectives and try and stick to them to avoid these common biases. Look beyond the surface-level and examine the reasons behind any market movements before going with the herd. See our article for tips on getting started on your investment journey.

“The stock market is a device for transferring money from the impatient to the patient… what you need is the temperament to control the urges that get other people into trouble in investing.” – Warren Buffet

What this means for a BrickX investor

Even in the micro-market of Brick-trading, the discussed behavioural biases are quite prevalent. People tend to have a subconscious bias towards properties in their home-state and are more likely to buy Bricks in properties listed at the top of the page. We will discuss these behavioural factors, how overall sentiment drives investing behaviour in more depth in an upcoming Whitepaper so keep your eyes peeled!